Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov is one of the most powerful and most feared men in Russia.

For more than a decade the Kremlin has relied on him to maintain order in Chechnya – the Russian North Caucasus republic he has ruled like a personal fiefdom.

Human rights groups have accused him of a string of abuses, including the forced disappearance of opponents, torture and the persecution of homosexuals.

Critics have linked Ramzan Kadyrov to several assassinations, some of them in Europe, but he denies involvement.

In 2015 he praised a Chechen security officer charged over the Moscow killing of Boris Nemtsov, who had been one of President Vladimir Putin’s most prominent critics.

Mr Kadyrov said Zaur Dadayev, a Russian Interior Ministry officer, was “sincerely devoted to Russia, ready to give his life for the motherland”. In 2017 Dadayev and four others were jailed for the murder.

A day after having praised Dadayev in 2015 Mr Kadyrov received a top award from President Putin.

He was given the Order of Honour for “work achievements, strenuous social activities and long conscientious service”.

In February thousands of people marched through Moscow to honour Nemtsov, five years after he was assassinated.

Loyalty to Kremlin

Mr Kadyrov has voiced strong support for the pro-Putin rebels in eastern Ukraine and for Russia’s annexation of Crimea. He is on the EU and US sanctions lists, which target many close associates of President Putin.

Earlier this month Facebook blocked his Instagram account, citing the US sanctions. He had more than 1.5 million followers on Instagram. His Facebook account was blocked in 2017.

Like Mr Putin, Ramzan Kadyrov adopts a macho image – he likes to be filmed posing with guns, fraternising with the military and supporting martial arts contests.

His alliance with Mr Putin goes back a long way.

In 2007, Mr Putin appointed him Chechen president. His father, Akhmad, who was elected president in a disputed vote in 2003 was assassinated a few months later in a bomb blast.

Ramzan Kadyrov already had a powerful, much-feared private militia called the “Kadyrovtsy”. Human rights groups accuse them of torture, kidnappings and assassinations in Chechnya, a mainly Muslim republic left devastated by war in the 1990s.

He had not always backed the Moscow leadership. In the early 1990s, he and his father joined the rebels fighting Russian forces in the first war for independence. They switched sides at the start of the second Chechen war in 1999.

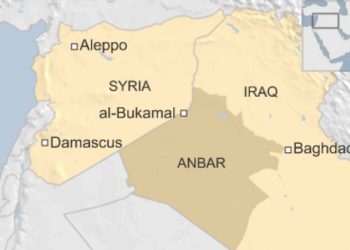

His ruthless methods against armed Islamists were useful for Russia as it tried to pacify the whole North Caucasus region, argues the BBC’s Murad Batal Shishani, a Chechen political analyst.

Islamist militancy became more acute in republics near Chechnya just as Mr Putin was trying to consolidate his presidency in Moscow.

Scorn for critics

Those who criticise official shortcomings in Chechnya are sometimes paraded humiliatingly on local state-controlled TV.

This month some doctors who complained about a lack of protective kit in the coronavirus crisis were shown later confessing that they had been mistaken.

In 2018 the BBC’s Steve Rosenberg questioned Mr Kadyrov about the accusations of human rights abuses levelled at him.

He answered scornfully: “The dog barks, but the caravan moves on. People who write these things about us: I don’t even consider them people.”

Rosenberg recalls the strongman’s dark sense of humour, from their first meeting in 2005.

As Mr Kadyrov strummed a guitar, our correspondent told him: “I play an instrument too – the piano.”

“Then you will play my piano, and if you play badly, I will put you in my jail,” Mr Kadyrov joked.

Previous killings

Cerwyn Moore, a North Caucasus expert at the UK’s Birmingham University, says Mr Kadyrov’s links to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) go back at least to 2000, when Mr Putin became president.

A top investigative journalist who condemned his methods – Anna Politkovskaya – was shot dead outside her Moscow apartment in 2006. Two men were jailed for life, though investigators failed to determine who ordered the killing.

In 2009, Russian human rights campaigner Natalia Estemirova was shot dead in the North Caucasus – another prominent critic of Mr Kadyrov’s harsh crackdown.

In Chechnya, Mr Kadyrov “has become a sort of cult leader – like some other post-Soviet leaders in Central Asia”, Mr Moore told the BBC.

“The outcome is you get ex-servicemen affiliated to him who do things that benefit him, much of which is very murky.”

There have also been killings abroad of former Kadyrov associates who fell foul of him, such as former bodyguard Umar Israilov in Vienna and Sulim Yamadayev in Dubai.